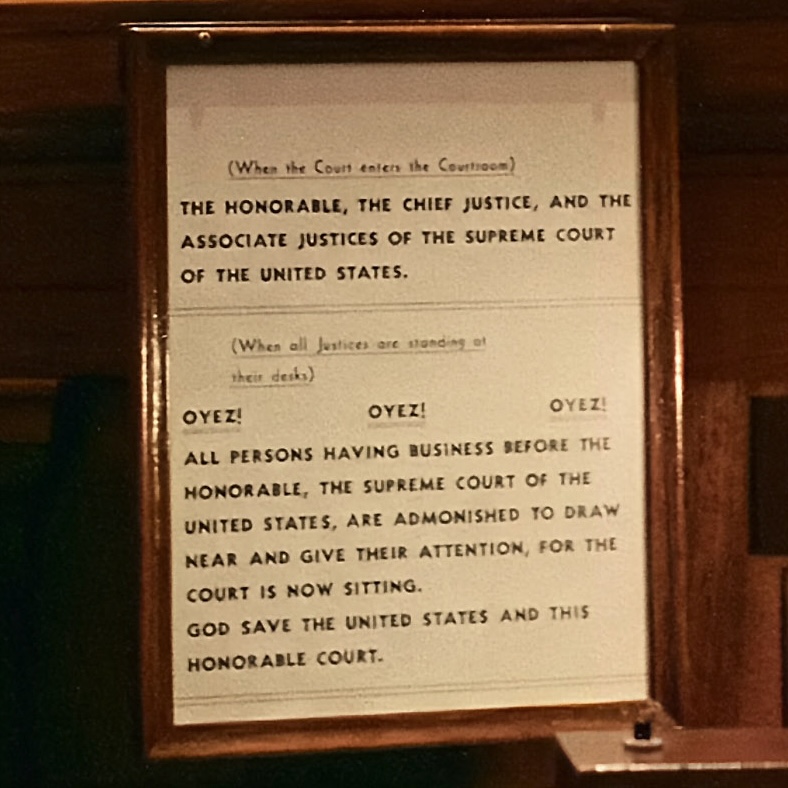

Oyez!

Oyez!

Oyez!

May 17, 1954:

Lawyers,

reporters,

and

spectators

have

gathered

at

the

U.S.

Supreme

Court

for

something

unusual.

The

Marshal

calls

the

room

to

order.

All

persons

having

business

before

the

Honorable,

the

Supreme

Court

of

the

United

States,

are

admonished

to

draw

near

and

give

their

attention.

Attention

isn't

in

short

supply.

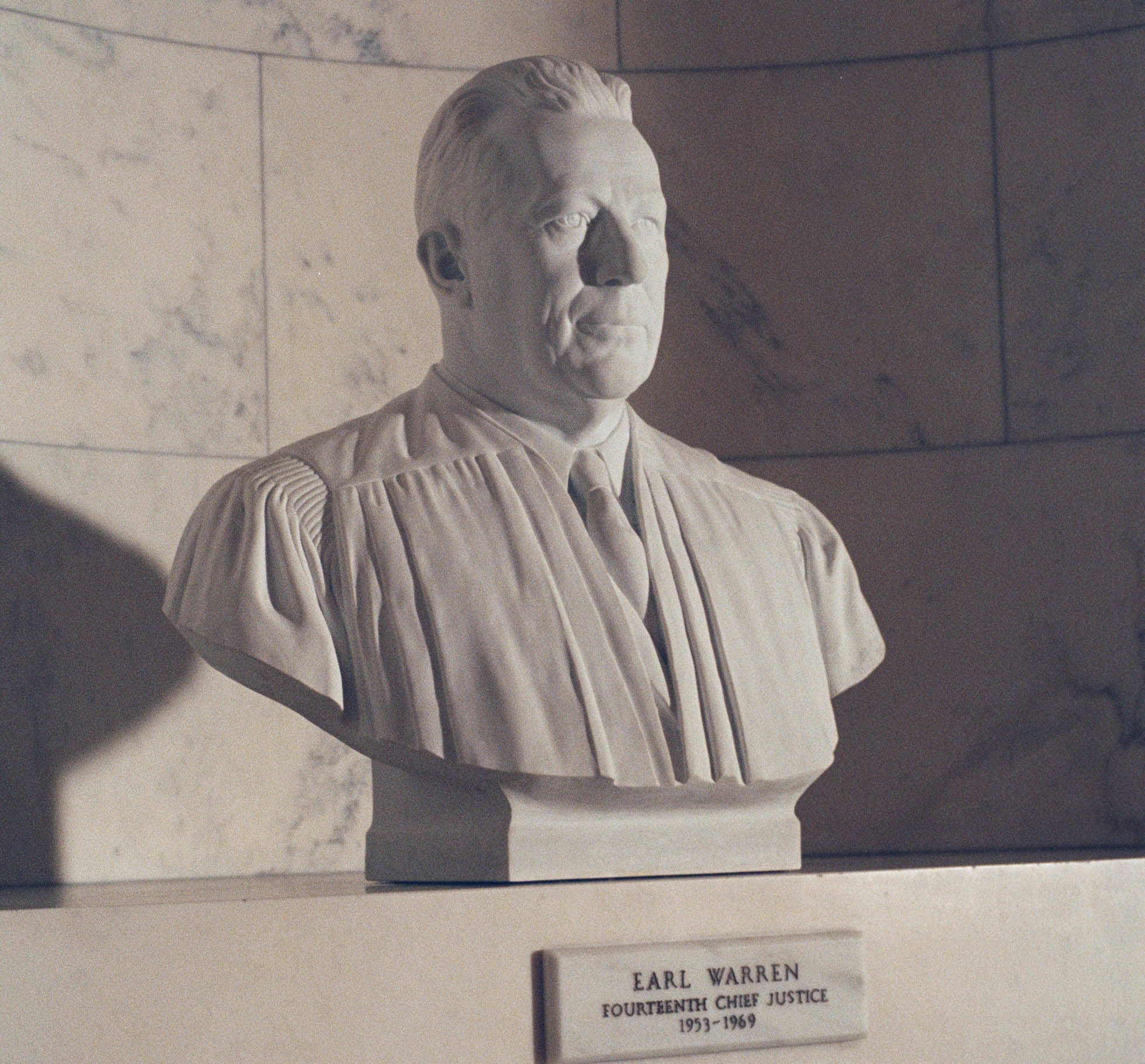

The

new

Chief

Justice

Earl

Warren

is

preparing

to

read

a

momentous

opinion -

one

that

will

cause

a

legal

and

cultural

earthquake

across

the

country.

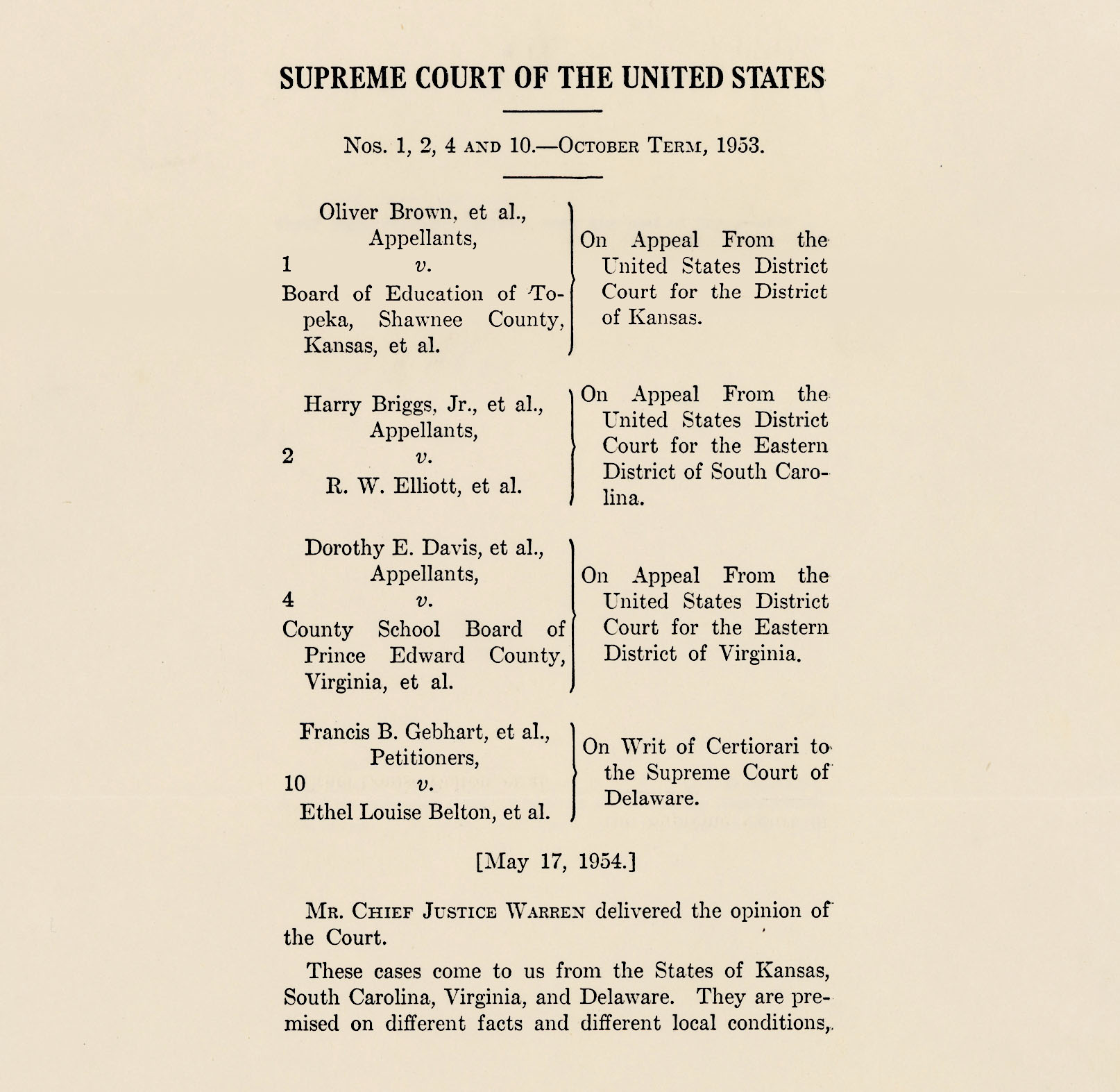

These

cases

come

to

us

from

the

states

of

Kansas,

South

Carolina,

Virginia,

and

Delaware.

In

fact,

there

are

four

cases

rolled

into

one.

Together,

they

pose

one

fundamental

question:

Does

the

Constitution

allow

states

to

segregate

public

schools?

The

opinion

is

known

by

the

first

case

before

the

court:

Brown

v.

the

Board

of

Education

of

Topeka,

Kansas,

or

Brown

v.

Board.

Warren

spends

a

few

minutes

explaining

the

aftermath

of

a

Supreme

Court

case

from

1896,

Plessy

v.

Ferguson.

It

established

a

doctrine

of

so-called

"separate

but

equal"

segregation.

But

at

this

point,

it's

still

unclear

which

way

the

justices

have

decided.

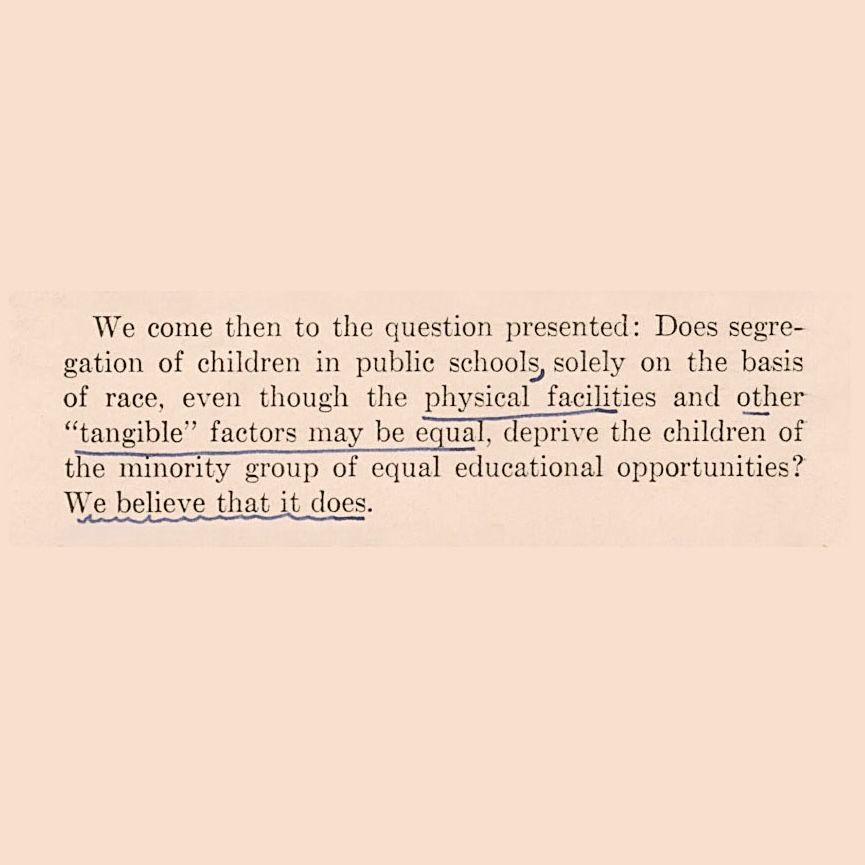

Then

Warren

gets

to

the

part

that

changed

history.

We

come

then

to

the

question

presented:

Does

segregation

of

children

in

public

schools

solely

on

the

basis

of

race,

even

though

the

physical

facilities

and

other

"tangible"

factors

may

be

equal,

deprive

the

children

of

the

minority

group

of

equal

educational

opportunities?

We

believe

that

it

does.

We

believe

that

it

does.

To

people

in

the

room,

those

five

words

signal

what's

about

to

come-

a

complete

reversal

of

a

doctrine

that

allowed

schoolchildren

to

be

educated

differently

based

on

the

color

of

their

skin.

Warren

continues:

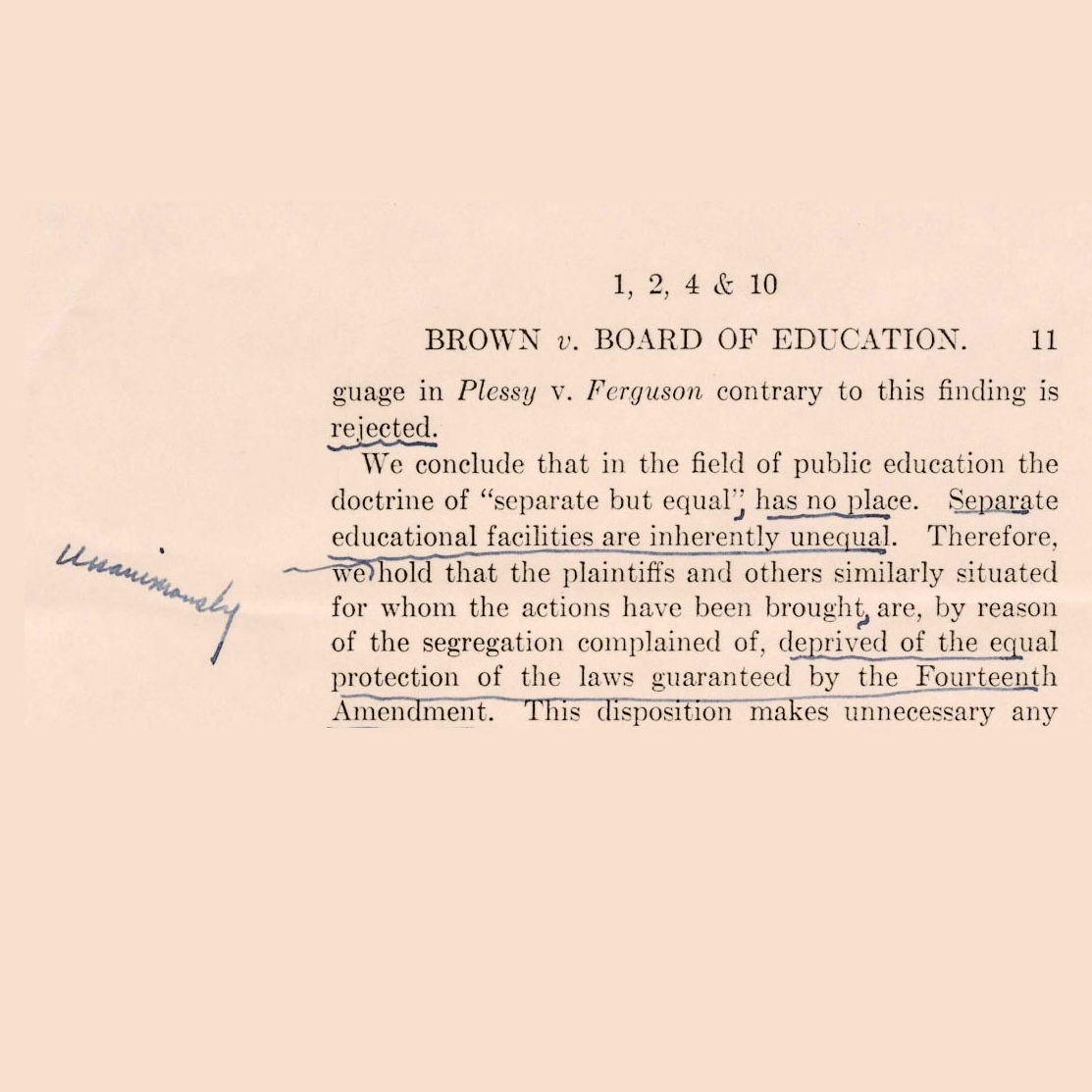

We

conclude

that,

in

the

field

of

public

education,

the

doctrine

of

"separate

but

equal"

has

no

place.

Separate

educational

facilities

are

inherently

unequal.

Therefore,

we

unanimously

hold

that

the

plaintiffs

and

others

similarly

situated

for

whom

the

actions

have

been

brought

are,

by

reason

of

the

segregation

complained

of,

deprived

of

the

equal

protection

of

the

laws

guaranteed

by

the

Fourteenth

Amendment.

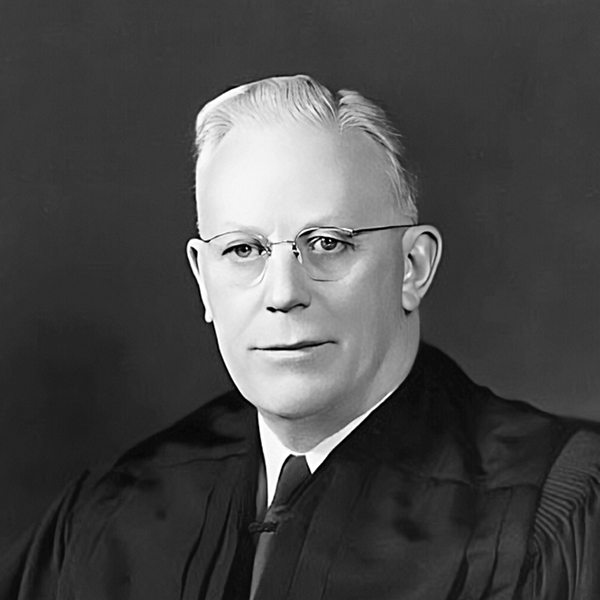

Earl

Warren

has

added

the

word

"unanimously."

People

in

the

room

gasp.

It

was

unexpected.

Let's

pause

here

for

a

quick

explanation

of

what

you're

hearing.

No

microphones

were

recording

Warren's

words

that

day

in

1954.

The

court

didn't

start

regular

recording

of

its

proceedings

until

the

following

year.

But

this

is

Warren's

voice.

Combining

other

recordings

of

the

Chief

Justice

with

an

actor's

performance,

you're

hearing

a

digitally

recreated

version

of

his

voice

reading

the

transcript

of

the

Brown

decision.

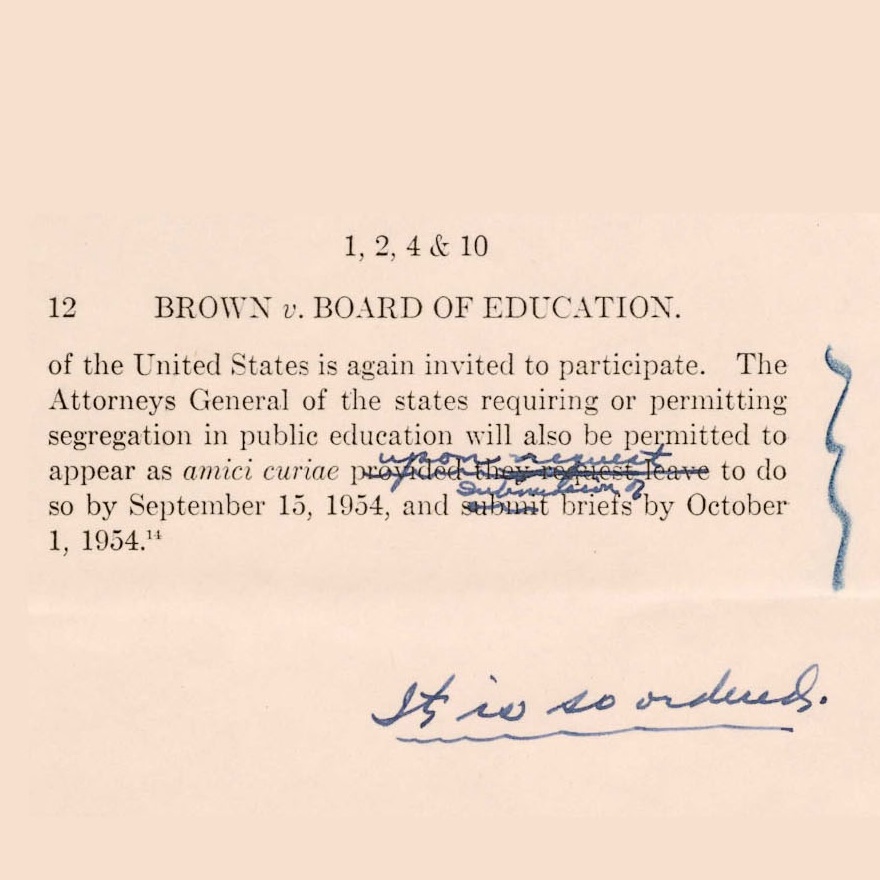

Warren's

opinion

ends

with

the

standard

language

indicating

that

the

Supreme

Court

expects

its

ruling

to

be

followed

across

the

country.

It

is

so

ordered.

If

only

it

were

that

simple.

For

decades

after

that

1954

ruling,

states

would

fight

the

Court's

order

to

integrate

schools.

And

even

today,

70

years

later,

forms

of

racial

segregation

remain

in

the

United

States.

But

Brown

v.

Board

marked

a

turning

point,

as

the

nation's

highest

court

began

dismantling

legal

segregation.

On

this

website,

we've

recreated

the

historic

oral

arguments

in

the

Brown

v.

Board

cases,

an

epic

clash

of

legal

titans

that

led

to

the

decision.

Using

the

latest

voice

replication

techniques,

we've

cloned

the

voices

of

key

participants.

That

includes

Thurgood

Marshall,

the

legendary

civil

rights

lawyer

who

won

this

case

and

who

went

on

to

become

the

first

Black

justice

on

the

Supreme

Court.

I

think

when

we

predict

what

might

happen,

I

know

in

the

South

where

I

spent

most

of

my

time,

you

will

see

white

and

colored

kids

going

down

the

road

together

to

school.

They

separate

and

go

to

different

schools,

and

they

come

out

and

they

play

together.

I

do

not

see

why

there

would

necessarily

be

any

trouble

if

they

went

to

school

together.

We

invite

you

to

explore

the

site

and

listen

in

on

these

oral

arguments,

which

no

one

outside

the

Court's

marble

walls

has

ever

heard

before.

--:--

--:--