Transcripts

Transcripts

Oliver Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, et al.

Washington, D. C.

Tuesday, December 09, 1952

Tuesday, December 09, 1952

No. 8

Appellants

OLIVER BROWN, MRS. RICHARD LAWTON, MRS. SADIE EMMANUEL, ET AL.

Appellees

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, SHAWNEE COUNTY, KANSAS, ET AL.

The above-entitled cause came on for oral argument at 1:35 p.m.

Before

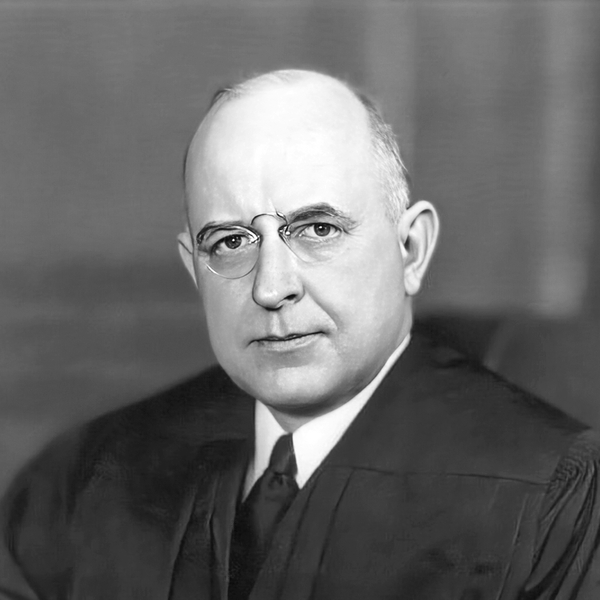

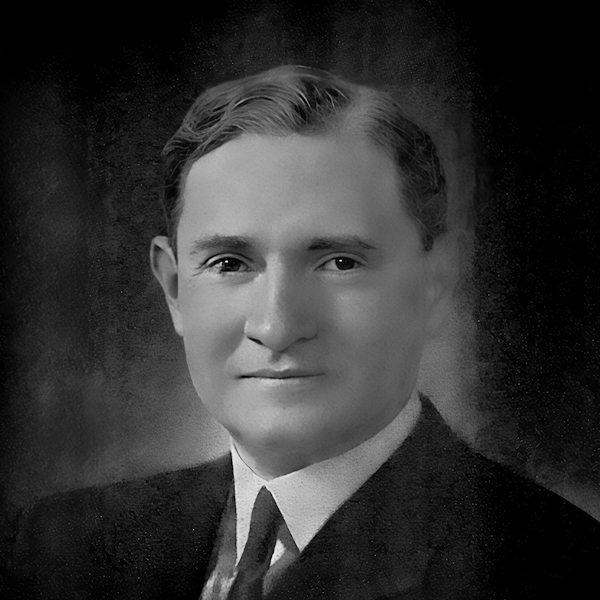

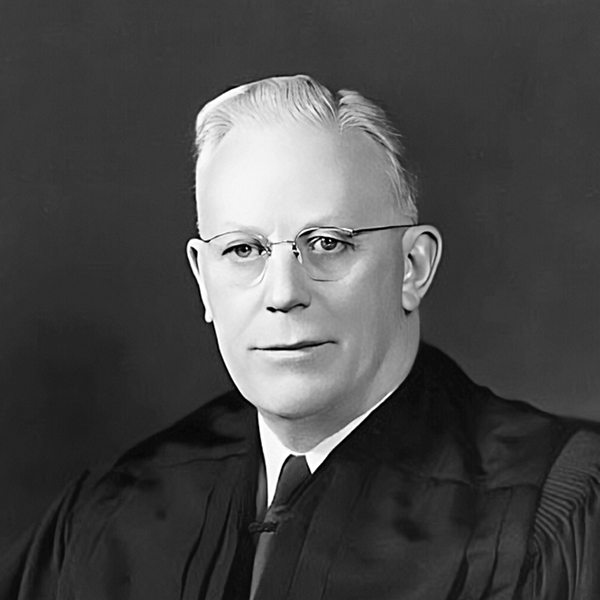

FRED M. VINSON, Chief Justice of the United States

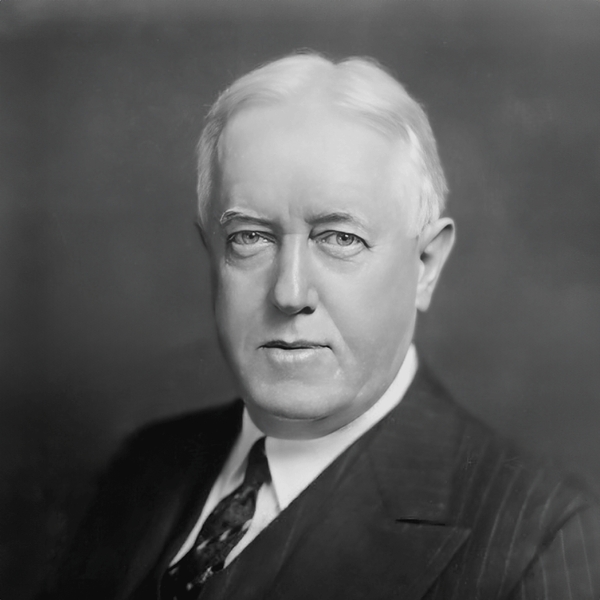

HUGO L. BLACK, Associate Justice

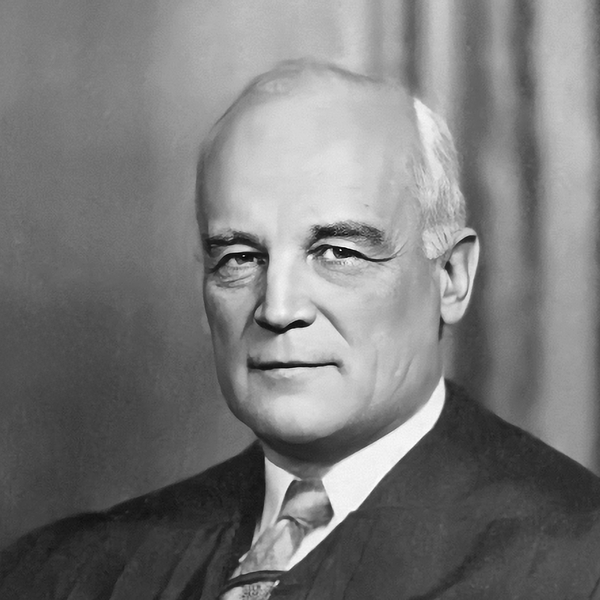

STANLEY F. REED, Associate Justice

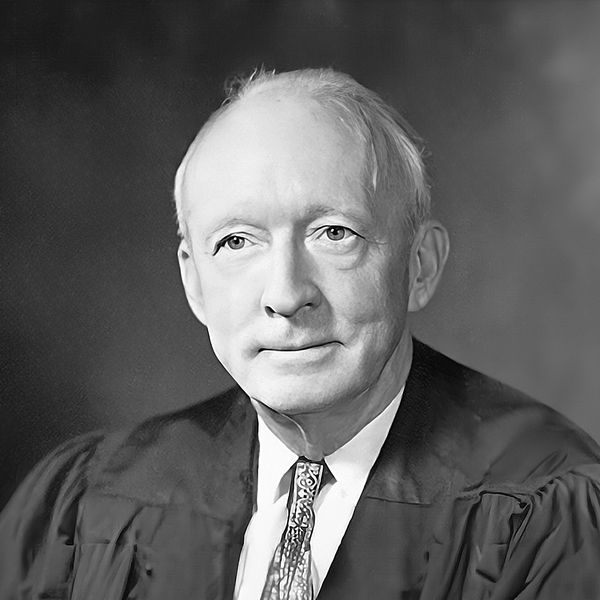

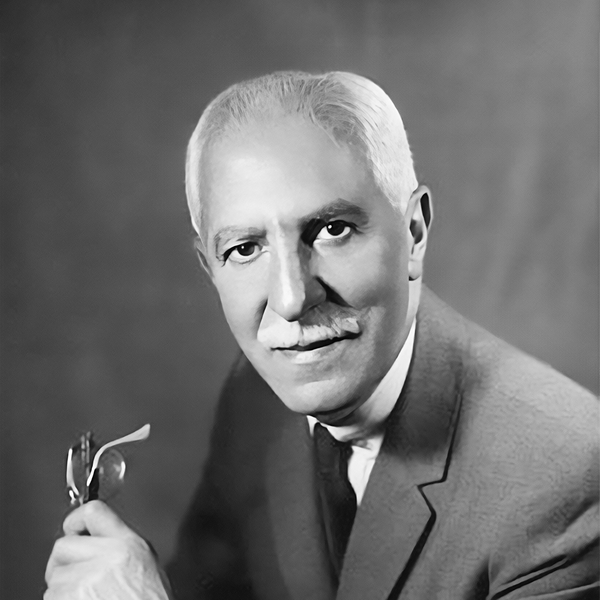

FELIX FRANKFURTER, Associate Justice

WILLIAM O. DOUGLAS, Associate Justice

ROBERT H. JACKSON, Associate Justice

HAROLD H. BURTON, Associate Justice

THOMAS C. CLARK, Associate Justice

SHERMAN MINTON, Associate Justice

HUGO L. BLACK, Associate Justice

STANLEY F. REED, Associate Justice

FELIX FRANKFURTER, Associate Justice

WILLIAM O. DOUGLAS, Associate Justice

ROBERT H. JACKSON, Associate Justice

HAROLD H. BURTON, Associate Justice

THOMAS C. CLARK, Associate Justice

SHERMAN MINTON, Associate Justice

Appearances

ROBERT L. CARTER, ESQ., on behalf of the Appellants.

PAUL E. WILSON, ESQ., on behalf of the Appellees.

PAUL E. WILSON, ESQ., on behalf of the Appellees.

PROCEEDINGS

Case No. 8, Oliver Brown and others v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas.

Counsel are present.

Mr. Carter.

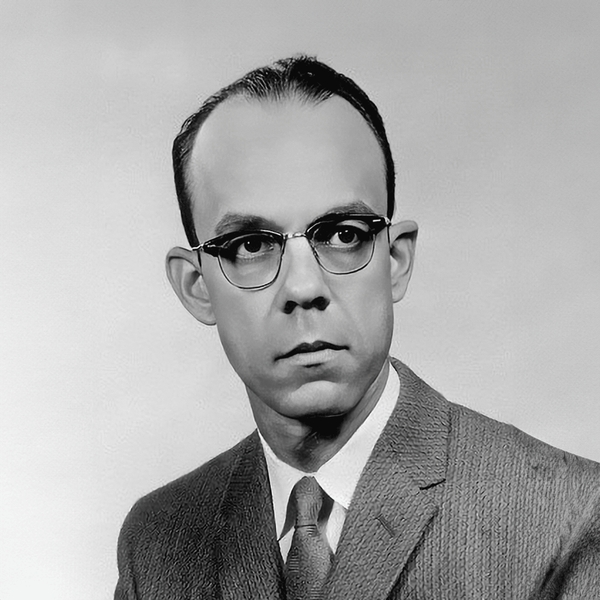

OPENING ARGUMENT OF ROBERT L. CARTER, ESQ.,

ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLANTS

ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLANTS

This case is here on direct appeal pursuant to Title 28, section 1253, 2101(b), from the final judgment of a statutory three-judge court, District Court for the District of Kansas, denying appellants' motion, application for a permanent injunction to restrain the enforcement of Chapter 72-1724 of the General Statutes of Kansas, on the grounds of that statute's fatal conflict with the requirements and guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The statute in question empowers boards of education in cities of the first class in Kansas to maintain and operate public elementary schools on a segregated basis, with the exception of Kansas City, Kansas, which is empowered to maintain segregated public high schools also.

The law of Kansas is clear, as construed by the highest court of that State, that except for this statutory authority, the appellees in this instance would have no power to make any distinction whatsoever in public schools among children on the basis of race and color; or, to put it another way, the law of Kansas is this: that it is a violation of state law for any state officer to use race as a factor in affording educational opportunities unless that authority is specifically, clearly, and expressly granted by the legislature.

The state cases, which are set forth and would set this out, are cited at page two of our brief.

Now, it is to be noted that this statute prohibits any type of color discrimination in high schools, with the exception of Kansas City, Kansas.

The Topeka school system is operated on a six-three-three plan: elementary schools going through the sixth grade, thereafter junior high schools through the ninth grade, and thereafter senior high schools.

So that in this instance, appellants are required to attend segregated elementary schools through the sixth grade, but thereafter they go to high schools without any determination being made as to which school they will attend on the basis of race. If appellants are of Negro origin, they are minors who are not eligible at the present time to attend the public elementary schools in Topeka.

The appellees are empowered by state law to maintain the public school system in Topeka, Kansas. The City of Topeka has been divided into eighteen territorial divisions for public school purposes. In each of these divisions appellees maintain one school for white residents; in addition, they maintain four segregated schools for Negroes.

It is the gravamen of our complaint—it was the gravamen of our complaint below, and it is the gravamen of our appeal here—that the appellees have deprived—we have been deprived of the equal protection of the laws where the statute requires appellants to attend public elementary schools on a segregated basis, because the act of separation and the act of segregation in and of itself denies them equal educational opportunities which the Fourteenth Amendment secures.

In the answer below, the appellees, the school board, defended this action on the ground that they were acting pursuant to the statute; that appellants were not entitled to attend the elementary schools in Kansas, the eighteen elementary schools, which they maintained for white children, solely because of race and color, and that they wouldn't be admitted into those schools because they were Negroes.

The State of Kansas in the court below, and in its brief filed here, defends the constitutionality of the statute in question, and affirmatively asserts that the state has the power to authorize the imposition of racial distinction for public school purposes.

The only state or federal constitutional limitation which the State of Kansas concedes on that power is that when these distinctions are imposed the school physical facilities for Negro children must be equal. With that limitation, they say that there can be no constitutional limitation on their power to impose racial distinctions.

A three-judge court was convened in the court below, pursuant to Title 28 of the United States Code, section 2281 and 2284, and there a trial on the merits took place.

At the trial, appellants introduced evidence designed to conclusively demonstrate that the act of segregation in and of itself made the educational opportunities which were provided in the four schools maintained for Negroes inferior to those in the eighteen schools which were maintained for white children, because of racial segregation imposed which severely handicapped Negro children in their pursuit of knowledge, and made it impossible for them to secure equal education.

In the course of the development of this uncontroverted testimony, appellants showed that they and other Negro children similarly situated were placed at a serious disadvantage with respect to their opportunity to develop citizenship skills, and that they were denied the opportunity to learn to adjust personally and socially in a setting comprising a cross section of the dominant population of the city.

It was testified that racial segregation, as practiced in the City of Topeka, tended to relegate appellants and their group to an inferior caste; that it lowered their level of aspiration; that it instilled feelings of insecurity and inferiority with them, and that it retarded their mental and educational development; and for these reasons, the testimony said, it was impossible for the Negro children who were set off in these four schools to secure, in fact or in law, an education which was equal to that available to white children in the eighteen elementary schools maintained for them.

On August 3, the district court filed its opinion, its findings of fact and its conclusions of law, and a final decree, all of which are set out at page 238 of the record.

We accept and adopt as our own all of the findings of fact of the court below, and I wish specifically to call to the Court's attention the findings which are findings four, five and six, which are set out at page 245, in which the court found that there was no material difference between the four schools maintained for Negroes and the eighteen schools maintained for white children with respect to physical facilities, the educational qualifications of teachers, and the courses of study prescribed.

Here we abandon any claim, in pressing our attack on the unconstitutionality of this statute—we abandon any claim of any constitutional inequality which comes from anything other than the act of segregation itself. In short, the sole basis for our appeal here on the constitutionality of the statute of Kansas is that it empowers the maintenance and operation of racially segregated schools, and under that basis we say, on the basis of the fact that the schools are segregated, that Negro children are denied equal protection of the laws, and they cannot secure equality in educational opportunity.

This the court found as a fact, and I will go into that finding, which is also set out on page 25 of the brief [Statement as to Jurisdiction], later in the development of my argument. But suffice it to say for this purpose that, although the court found that racial segregation created educational inequality in fact, it concluded, as a matter of law, that the only type of educational inequality which was cognizable under the Constitution was an educational inequality which stems from material and physical factors; and absent any inequality of that level, the court said:

We are bound by Plessy v. Ferguson, and Gong Lum v. Rice to hold in appellees' favor and uphold the constitutionality of that statute.

The statute in question empowers boards of education in cities of the first class in Kansas to maintain and operate public elementary schools on a segregated basis, with the exception of Kansas City, Kansas, which is empowered to maintain segregated public high schools also.

The law of Kansas is clear, as construed by the highest court of that State, that except for this statutory authority, the appellees in this instance would have no power to make any distinction whatsoever in public schools among children on the basis of race and color; or, to put it another way, the law of Kansas is this: that it is a violation of state law for any state officer to use race as a factor in affording educational opportunities unless that authority is specifically, clearly, and expressly granted by the legislature.

The state cases, which are set forth and would set this out, are cited at page two of our brief.

Now, it is to be noted that this statute prohibits any type of color discrimination in high schools, with the exception of Kansas City, Kansas.

The Topeka school system is operated on a six-three-three plan: elementary schools going through the sixth grade, thereafter junior high schools through the ninth grade, and thereafter senior high schools.

So that in this instance, appellants are required to attend segregated elementary schools through the sixth grade, but thereafter they go to high schools without any determination being made as to which school they will attend on the basis of race. If appellants are of Negro origin, they are minors who are not eligible at the present time to attend the public elementary schools in Topeka.

The appellees are empowered by state law to maintain the public school system in Topeka, Kansas. The City of Topeka has been divided into eighteen territorial divisions for public school purposes. In each of these divisions appellees maintain one school for white residents; in addition, they maintain four segregated schools for Negroes.

It is the gravamen of our complaint—it was the gravamen of our complaint below, and it is the gravamen of our appeal here—that the appellees have deprived—we have been deprived of the equal protection of the laws where the statute requires appellants to attend public elementary schools on a segregated basis, because the act of separation and the act of segregation in and of itself denies them equal educational opportunities which the Fourteenth Amendment secures.

In the answer below, the appellees, the school board, defended this action on the ground that they were acting pursuant to the statute; that appellants were not entitled to attend the elementary schools in Kansas, the eighteen elementary schools, which they maintained for white children, solely because of race and color, and that they wouldn't be admitted into those schools because they were Negroes.

The State of Kansas in the court below, and in its brief filed here, defends the constitutionality of the statute in question, and affirmatively asserts that the state has the power to authorize the imposition of racial distinction for public school purposes.

The only state or federal constitutional limitation which the State of Kansas concedes on that power is that when these distinctions are imposed the school physical facilities for Negro children must be equal. With that limitation, they say that there can be no constitutional limitation on their power to impose racial distinctions.

A three-judge court was convened in the court below, pursuant to Title 28 of the United States Code, section 2281 and 2284, and there a trial on the merits took place.

At the trial, appellants introduced evidence designed to conclusively demonstrate that the act of segregation in and of itself made the educational opportunities which were provided in the four schools maintained for Negroes inferior to those in the eighteen schools which were maintained for white children, because of racial segregation imposed which severely handicapped Negro children in their pursuit of knowledge, and made it impossible for them to secure equal education.

In the course of the development of this uncontroverted testimony, appellants showed that they and other Negro children similarly situated were placed at a serious disadvantage with respect to their opportunity to develop citizenship skills, and that they were denied the opportunity to learn to adjust personally and socially in a setting comprising a cross section of the dominant population of the city.

It was testified that racial segregation, as practiced in the City of Topeka, tended to relegate appellants and their group to an inferior caste; that it lowered their level of aspiration; that it instilled feelings of insecurity and inferiority with them, and that it retarded their mental and educational development; and for these reasons, the testimony said, it was impossible for the Negro children who were set off in these four schools to secure, in fact or in law, an education which was equal to that available to white children in the eighteen elementary schools maintained for them.

On August 3, the district court filed its opinion, its findings of fact and its conclusions of law, and a final decree, all of which are set out at page 238 of the record.

We accept and adopt as our own all of the findings of fact of the court below, and I wish specifically to call to the Court's attention the findings which are findings four, five and six, which are set out at page 245, in which the court found that there was no material difference between the four schools maintained for Negroes and the eighteen schools maintained for white children with respect to physical facilities, the educational qualifications of teachers, and the courses of study prescribed.

Here we abandon any claim, in pressing our attack on the unconstitutionality of this statute—we abandon any claim of any constitutional inequality which comes from anything other than the act of segregation itself. In short, the sole basis for our appeal here on the constitutionality of the statute of Kansas is that it empowers the maintenance and operation of racially segregated schools, and under that basis we say, on the basis of the fact that the schools are segregated, that Negro children are denied equal protection of the laws, and they cannot secure equality in educational opportunity.

This the court found as a fact, and I will go into that finding, which is also set out on page 25 of the brief [Statement as to Jurisdiction], later in the development of my argument. But suffice it to say for this purpose that, although the court found that racial segregation created educational inequality in fact, it concluded, as a matter of law, that the only type of educational inequality which was cognizable under the Constitution was an educational inequality which stems from material and physical factors; and absent any inequality of that level, the court said:

We are bound by Plessy v. Ferguson, and Gong Lum v. Rice to hold in appellees' favor and uphold the constitutionality of that statute.

We have one fundamental contention which we will seek to develop in the course of this argument, and that contention is that no state has any authority under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to use race as a factor in affording educational opportunities among its citizens.

We say that for two reasons: First, we say that a division of citizens by the states for public school purposes on the basis of race and color effects an unlawful and an unconstitutional classification within the meaning of the equal protection clause; and, secondly, we say that where public school attendance is determined on the basis of race and color, that it is impossible for Negro children to secure equal educational opportunities within the meaning of the equal protection of the laws.

With regard to the first basis of our attack on the statute, Kansas has authorized, under certain conditions, certain boards of education to divide its schools at the elementary school level for the purpose of giving them educational opportunities.

It is our position that any legislative or governmental classification must fall with an even hand on all persons similarly situated. This Court has long held that this is the law with respect to a lawful classification, and in order to assure that this evenhandedness of the law in terms of classifications exists, this Court has set standards which say that where the legislature of a state seeks to make a classification among persons, that that classification and those distinctions must rest upon some differentiation fairly related to the object which the state seeks to regulate.

Now, in this case the Negro children are—and other Negro children similarly situated are—put in one category for public school purposes, solely on the basis of race and color, and white children are put in another category for the purpose of determining what schools they will attend.

With regard to the first basis of our attack on the statute, Kansas has authorized, under certain conditions, certain boards of education to divide its schools at the elementary school level for the purpose of giving them educational opportunities.

It is our position that any legislative or governmental classification must fall with an even hand on all persons similarly situated. This Court has long held that this is the law with respect to a lawful classification, and in order to assure that this evenhandedness of the law in terms of classifications exists, this Court has set standards which say that where the legislature of a state seeks to make a classification among persons, that that classification and those distinctions must rest upon some differentiation fairly related to the object which the state seeks to regulate.

Now, in this case the Negro children are—and other Negro children similarly situated are—put in one category for public school purposes, solely on the basis of race and color, and white children are put in another category for the purpose of determining what schools they will attend.

Mr. Carter, I do not know whether I have followed you or all the facts on this. Was there a finding that the only basis of classification was race or color?

It was admitted—the appellees admitted in their answer—that the only reason that they would not permit Negro children to attend the eighteen white schools was because they were Negro.

Then we accept on this record that the only showing is that the classification here was solely on race and color?

Yes, sir. I think the state itself concedes this is so in its brief.

Now, we say that the only basis for this division is race, and that under the decisions of this Court that no state can use race, and race alone, as a basis upon which to ground any legislative—any lawful constitutional authority—and particularly this Court has indicated in a number of opinions that this is so because it is not felt that race is a reasonable basis upon which to ground acts; it is not a real differentiation, and it is not relevant and, in fact, this Court has indicated that race is arbitrary and an irrational standard, so that I would also like to point out, if I may, going to and quoting the statute, that the statute itself shows that this is so. I am reading from the quote of the statute from page three of our brief. The statute says:

The Board of Education … may organize and maintain separate schools for the education of white and colored children, including the high schools in Kansas City, Kansas; no discrimination on account of color shall be made in high schools except as provided herein.

We say that on the face of the statute this is explicit recognition of the fact that the authorization which the state gave to cities of the first class, and so forth, to make this segregation on the basis of race, carried with it the necessary fact that they were permitted to discriminate on the basis of race and color, and that the statute recognizes that these two things are interchangeable and cannot be separated.

Now, without further belaboring our classification argument, our theory is that if the normal rules of classification, the equal protection doctrine of classification, apply to this case—and we say they should be applied—that this statute is fatally defective, and that on this ground, and this ground alone, the statute should be struck down.

We also contend, as I indicated, a second ground for the unconstitutionality of the statute. A second part of the main contention is that this type of segregation makes it impossible for Negro children and appellants in this case to receive equal educational opportunities; and that in this case the court below found this to be so as a fact; and I would turn again to quote on page 245 of the record, finding No. 8, where the court in its findings said—and I quote:

Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law; for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to restrain the educational and mental development of Negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racially integrated school system.

Now, as we had indicated before, this finding is amply supported by the uncontroverted testimony, and we feel that what the court did in this case in approaching this finding was that it made the same approach on a factual basis that this Court made in the McLaurin and Sweatt cases.

It is our contention, our view, that when this Court was confronted with the question of whether McLaurin and Sweatt were afforded equal educational opportunities, that it looked at the restrictions imposed to find out whether or not they in any way impaired the quality of education which was offered and, upon finding that the quality of education that had been offered under the segregated conditions—that this Court held in both instances that those racial restrictions could not stand.

The court below, based on this finding, starts its examination in this same way. It finds that the restrictions which the appellants complained of place them and other Negro children in the class at a disadvantage with respect to the quality of education which they would receive, and that as a result of these restrictions Negro children are—the development of their minds and the learning process is impaired and damaged.

We take the position that where there exists educational inequality, in fact, that it necessarily follows that educational inequality in the law is also present.

But the court below felt, as I indicated before, that the only concern of the Constitution with the question of educational equality was that the physical facilities afforded had to be equal; and absent any inequality with regard to physical facilities, they say, "We are bound by Plessy v. Ferguson, and Gong Lum v. Rice."

It is also clear from the court's opinion that it was in a great deal of confusion and doubt and, perhaps, even in torture in reaching these results.

I would again like to quote from the record the court's opinion, on page 243, and the court says:

If segregation within a school as in the McLaurin case is a. denial of due process, it is difficult to see why segregation in separate schools would not result in the same denial. Or if the denial of the right to commingle with the majority group in higher institutions of learning as in the Sweatt case and gain the educational advantages resulting therefrom is lack of due process, it is difficult to see why such denial would not result in the same lack of due process if practiced in the lower grades.

We say that but for the constraint which the court feels was imposed upon it by the McLaurin case—

Now, we say that the only basis for this division is race, and that under the decisions of this Court that no state can use race, and race alone, as a basis upon which to ground any legislative—any lawful constitutional authority—and particularly this Court has indicated in a number of opinions that this is so because it is not felt that race is a reasonable basis upon which to ground acts; it is not a real differentiation, and it is not relevant and, in fact, this Court has indicated that race is arbitrary and an irrational standard, so that I would also like to point out, if I may, going to and quoting the statute, that the statute itself shows that this is so. I am reading from the quote of the statute from page three of our brief. The statute says:

The Board of Education … may organize and maintain separate schools for the education of white and colored children, including the high schools in Kansas City, Kansas; no discrimination on account of color shall be made in high schools except as provided herein.

We say that on the face of the statute this is explicit recognition of the fact that the authorization which the state gave to cities of the first class, and so forth, to make this segregation on the basis of race, carried with it the necessary fact that they were permitted to discriminate on the basis of race and color, and that the statute recognizes that these two things are interchangeable and cannot be separated.

Now, without further belaboring our classification argument, our theory is that if the normal rules of classification, the equal protection doctrine of classification, apply to this case—and we say they should be applied—that this statute is fatally defective, and that on this ground, and this ground alone, the statute should be struck down.

We also contend, as I indicated, a second ground for the unconstitutionality of the statute. A second part of the main contention is that this type of segregation makes it impossible for Negro children and appellants in this case to receive equal educational opportunities; and that in this case the court below found this to be so as a fact; and I would turn again to quote on page 245 of the record, finding No. 8, where the court in its findings said—and I quote:

Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law; for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to restrain the educational and mental development of Negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racially integrated school system.

Now, as we had indicated before, this finding is amply supported by the uncontroverted testimony, and we feel that what the court did in this case in approaching this finding was that it made the same approach on a factual basis that this Court made in the McLaurin and Sweatt cases.

It is our contention, our view, that when this Court was confronted with the question of whether McLaurin and Sweatt were afforded equal educational opportunities, that it looked at the restrictions imposed to find out whether or not they in any way impaired the quality of education which was offered and, upon finding that the quality of education that had been offered under the segregated conditions—that this Court held in both instances that those racial restrictions could not stand.

The court below, based on this finding, starts its examination in this same way. It finds that the restrictions which the appellants complained of place them and other Negro children in the class at a disadvantage with respect to the quality of education which they would receive, and that as a result of these restrictions Negro children are—the development of their minds and the learning process is impaired and damaged.

We take the position that where there exists educational inequality, in fact, that it necessarily follows that educational inequality in the law is also present.

But the court below felt, as I indicated before, that the only concern of the Constitution with the question of educational equality was that the physical facilities afforded had to be equal; and absent any inequality with regard to physical facilities, they say, "We are bound by Plessy v. Ferguson, and Gong Lum v. Rice."

It is also clear from the court's opinion that it was in a great deal of confusion and doubt and, perhaps, even in torture in reaching these results.

I would again like to quote from the record the court's opinion, on page 243, and the court says:

If segregation within a school as in the McLaurin case is a. denial of due process, it is difficult to see why segregation in separate schools would not result in the same denial. Or if the denial of the right to commingle with the majority group in higher institutions of learning as in the Sweatt case and gain the educational advantages resulting therefrom is lack of due process, it is difficult to see why such denial would not result in the same lack of due process if practiced in the lower grades.

We say that but for the constraint which the court feels was imposed upon it by the McLaurin case—

We will recess for lunch.

A short recess was taken.

AFTERNOON SESSION

Mr. Carter?

Just before the recess, I was attempting to show that in the opinion of the court below, that it was clear from the opinion that the court felt that the rule of law applicable in the McLaurin and Sweatt cases should apply here, but felt that it was constrained and prevented from doing that by virtue of Plessy v. Ferguson and Gong Lum v. Rice. We believe that the court below was wrong in this conclusion. We think that the rules of law applicable to McLaurin and Sweatt do apply, and that there are no decisions of this Court which require a contrary result.

Was there any evidence in the record to show the inability, the lesser ability, of the child in the segregated schools?

Yes, sir, there was a great deal of testimony on the impact of racial distinctions and segregation on the emotional and mental development of a child. Now, this is, in summary, Finding 8 of the court, a summarization of the evidence that we introduced on that.

And the findings go to the ability to learn or merely on the emotional reaction?

The finding says that—

I know about the finding, but the evidence?

The evidence, yes, sir. The evidence went to the fact that in the segregated school, because of these emotional impacts that segregation has, that it does impair the ability to learn, that you are not able to learn as well as you do if you were in a mixed school; and that, further than that, you are barred from contact with members of the dominant group and, therefore, your total educational content is somewhat lower than it would be ordinarily.

Would those citations be in your brief on page nine?

Yes, sir. In fact, what we attempted to do was to pick up in summary and refer the Court to the record of the various disabilities to which our witnesses testified, and we covered the question of the content of education. They are all set out on page nine of our brief as citations.

It is your position that there is a great deal more to the educational process even in the elementary schools than what you read in the books?

Yes, sir, that is precisely the point.

And it is on that basis which makes a real difference whether it is segregated or not?

Yes, sir. We say that the question of your physical facilities is not enough. The Constitution does not, in terms of protecting, giving equal protection of the laws with regard to equal educational opportunities, does not stop with the fact that you have equal physical facilities, but it covers the whole educational process.

The findings in this case did not stop with equal physical facilities, did they?

No, sir, the findings did not stop, but went beyond that. But, as I indicated, the Court did not feel that it could go in the law beyond physical facilities.

Of the two cases which the court below indicates have kept it from ruling as a matter of law in this case that educational, equal educational, opportunities were not afforded, the first is the Plessy v. Ferguson case.

Of the two cases which the court below indicates have kept it from ruling as a matter of law in this case that educational, equal educational, opportunities were not afforded, the first is the Plessy v. Ferguson case.

It is our position that Plessy v. Ferguson is not in point here; that it had nothing to do with educational opportunities whatsoever. We further take the position that, whatever the court below may have felt about the reach of the Plessy case, that this Court in the Sweatt case made it absolutely clear that Plessy v. Ferguson had nothing to do with the question of education.

The Court, in its opinion, after discussing the Sipuel case, the Fisher case, and the Gaines case, in the Sweatt opinion said that these are the only cases in this Court which control the issue of racial distinction in state-supported graduate and professional education. We think this was a pointed and deliberate omission in Plessy, and that the Court is saying that Plessy v. Ferguson certainly has nothing to do with the validity of racial distinctions in graduate and professional schools.

By the same logic, we say that, since Plessy had nothing to do with the higher level of education, it certainly has nothing to do with equal educational opportunities in the elementary grades. For that reason we think that Plessy need not be considered; that it has nothing to do with this case, and it is out of the case entirely.

By the same logic, we say that, since Plessy had nothing to do with the higher level of education, it certainly has nothing to do with equal educational opportunities in the elementary grades. For that reason we think that Plessy need not be considered; that it has nothing to do with this case, and it is out of the case entirely.

Well, in regard to the findings, it was found that the physical facilities, curricula, courses of study, qualifications and quality of teachers, as well as other educational facilities in the two sets of schools are comparable?

Yes, sir.

And the only item of discrimination, an item of discrimination, was transportation by bus for the colored students without that facility for the white students.

That is true. But the court—these are the physical factors that the court found; and then the court went on to show how segregation made the educational opportunities inferior, and this, we think, is the heart of our case.

That is all that you really have here to base your segregation issue upon.

That is right.

I mean, of course, you could have the issue as to equal facilities on the other, but so far as all the other physical facilities, curricula, teachers, and transportation and all that, and so forth, there is a finding that they are equal?

Yes, sir, and we do not controvert that finding.

The other case that the court below cited was the Gong Lum v. Rice case. We do not think that that case is controlling here either. In that case it is true that what was involved was racial distinction in the elementary grades.

The other case that the court below cited was the Gong Lum v. Rice case. We do not think that that case is controlling here either. In that case it is true that what was involved was racial distinction in the elementary grades.

Was that a Chinese student?

That was the Chinese student. But we think that case is so different from our case that it cannot control the decision in this case, because there the issue which was raised by petitioner of Chinese origin was that she did not at all contest the state's power to enforce a racial classification. She conceded that the state had such power. What petitioner was objecting to was the fact that, as a Chinese, a child of Chinese origin, that she was required to have contact with Negroes for school purposes which, under the segregation laws of Mississippi, white children were protected against. She said that if—her contention was that if there were some benefits or harms that would flow to white children from being forced to have contacts with Negroes, that she had an equal right to benefit or to be free of that harm from such contact, and that to require her to be classified among Negroes for school purpose was a denial to her of the equal protection of the laws.

Our contention is that in that instance that case cannot control a decision when here we are contesting the power of the state to make any classification whatsoever, and we think that what the court did below, this Court, in defining what was the issue in this case, said that the question was whether an American citizen of Chinese origin is denied equal protection and classed among the colored races for public school purposes, and furnished equal educational opportunities. It said that, were this a new question:

We would think it would need our full consideration, and it would be necessary for full argument, but it is not a new question. It is the same question that we have many times decided to be within the purview of the States, without the intervention of the Federal Constitution.

Now, we do not believe that Gong Lum can be considered as a precedent contrary to the position we take here. Certainly it cannot be conceded as such a precedent until this Court, when the issue is squarely presented to it, on the question of the power of the state, examines the question and makes a determination in the state's favor; and only in that instance do we feel that Gong Lum can be any authority on this question.

Our contention is that in that instance that case cannot control a decision when here we are contesting the power of the state to make any classification whatsoever, and we think that what the court did below, this Court, in defining what was the issue in this case, said that the question was whether an American citizen of Chinese origin is denied equal protection and classed among the colored races for public school purposes, and furnished equal educational opportunities. It said that, were this a new question:

We would think it would need our full consideration, and it would be necessary for full argument, but it is not a new question. It is the same question that we have many times decided to be within the purview of the States, without the intervention of the Federal Constitution.

Now, we do not believe that Gong Lum can be considered as a precedent contrary to the position we take here. Certainly it cannot be conceded as such a precedent until this Court, when the issue is squarely presented to it, on the question of the power of the state, examines the question and makes a determination in the state's favor; and only in that instance do we feel that Gong Lum can be any authority on this question.

Mr. Carter, while what you say may be so, nevertheless, in its opinion the Court in Gong Lum did rest on the fact that this issue had been settled by a large body of adjudications going back to what was or might fairly have been called an abolitionist state, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, going back to the Roberts case.

Yes, sir.

I want to ask you—and may I say, particularly in a case of this sort, a question does not imply an answer; a question merely implies an eager desire for information—I want to ask you whether in the light of that fact—this was a unanimous opinion of the Court which at the time had on its membership Justice Holmes, Justice Brandeis, Justice Stone—and I am picking those out not invidiously, but as judges who gave great evidence of being very sensitive and alert to questions of so-called civil liberties—and I should like to ask you whether you think that decision rested on the concession by the petitioner in that case, and the problem of segregation was not involved and, in fact, that underlay the whole decision, the whole adjudication—whether you think a man like Justice Brandeis would have been foreclosed by the concession of the parties?

Well, Your Honor, in all honesty, I would say that only partially would I consider that to be true. I think that what the Court did in Gong Lum, the Court was presented with the issue or the question, and it assumed that facilities were equal; and the Court at that time, with regard to this issue which was raised, although they conceded the power and did not have to make any full examination, it felt after reviewing those other decisions that the only question that they would have to consider or settle was the question of equal facilities.

Yes. But the Court took as settled by a long course of decisions that this question was many times decided, that this power was within the constitutional power of the state legislatures, this power of segregation.

Yes, sir.

The more specific question I would like to put to you is this: Do we not have to face the fact that what you are challenging is something that was written into the public law and adjudications of courts, including this Court, by a large body of decisions and, therefore, the question arises whether, and under what circumstances, this Court should now upset so long a course of decisions? Don't we have to face that, instead of chipping away and saying, "This was dictum," and "This was a mild dictum," and "This was a strong dictum," and is anything to be gained by concealing that central fact, that central issue?

Well, I do not think, Your Honor, that you have to face that issue. My view is that, with regard to this particular question this Court decided with Sweatt v. Painter—in Sweatt v. Painter in this Court, the only decision here which was decided on the question of "separate but equal" was a dictum coming out from Plessy v. Ferguson, and this Court in the Sweatt case, it seems to me very carefully to have decided that it did not have to face the question because Plessy v. Ferguson was not involved.

I think in this particular case the only decision of this Court which can be said to have decided a question of the validity of racial distinction in elementary schools is this case that I am discussing. Now, I think that, in view of the concession, in view of the fact that the Court felt this was not a case of first impression, although I think it was and is a case of first impression in this Court at the time it came here, that this Court did not give the arguments at all a full consideration which we think that they require.

I think in this particular case the only decision of this Court which can be said to have decided a question of the validity of racial distinction in elementary schools is this case that I am discussing. Now, I think that, in view of the concession, in view of the fact that the Court felt this was not a case of first impression, although I think it was and is a case of first impression in this Court at the time it came here, that this Court did not give the arguments at all a full consideration which we think that they require.

You are quite right in suggesting that this question explicitly as to segregation in the primary grades has not been adjudicated by this Court. This question is, in that frame, in that explicitness, unembarrassed by physical inequalities, and so on, before the Court for the first time.

But a long course of legislation by the states, and a long course of utterances by this Court and other courts in dealing with the subject, from the point of view of relevance as to whether a thing is or is not within the prohibition of the Fourteenth Amendment, is from my point of view almost as impressive as a single decision, which does not mean that I would be controlled in a constitutional case by a direct adjudication; but I do think we have to face in this case the fact that we are dealing with a long-established historical practice by the states, and the assumption of the exercise of power which not only was written on the statute books, but has been confirmed and adjudicated by state courts, as well as by expressions of this Court.

But a long course of legislation by the states, and a long course of utterances by this Court and other courts in dealing with the subject, from the point of view of relevance as to whether a thing is or is not within the prohibition of the Fourteenth Amendment, is from my point of view almost as impressive as a single decision, which does not mean that I would be controlled in a constitutional case by a direct adjudication; but I do think we have to face in this case the fact that we are dealing with a long-established historical practice by the states, and the assumption of the exercise of power which not only was written on the statute books, but has been confirmed and adjudicated by state courts, as well as by expressions of this Court.

Well, Mr. Justice Frankfurter, I would say on that that I was attempting here to take the narrow position with regard to this case, and to approach it in a way that I thought the Court approached the decision in Sweatt and McLaurin. I have no hesitancy in saying to the Court that if they do not agree that the decision can be handed down in our favor on this basis of this approach, that I have no hesitancy in saying that the issue of "separate but equal" should be faced and ought to be faced, and that in our view the "separate but equal" doctrine should be overruled. But as I said before, as the Court apparently approached Sweatt and McLaurin, it did not feel it had to meet that issue, and we do not feel it has to meet it here. But if the Court has reached a contrary conclusion in regard to it, then we, of course, take the position that the "separate but equal" doctrine should be squarely overruled.

May I trouble you to clarify that? Do I understand from what you have just said that you think this Kansas law is bad on the record, is bad in the Kansas case, on the "separate but equal" doctrine, and that even by that test this law must fall?

No, sir, I think—

Then why do we not have to face the "separate but equal" doctrine?

Because insofar as this Court is concerned, as I have indicated before, this Court, with the exception of Gong Lum, has not at the elementary level adopted the "separate but equal" doctrine. There is no decision in this Court, unless the Court feels that Gong Lum v. Riceis that decision.

As I attempted to indicate before, that was a case of first impression, although the Court did not seem to think it was, and that here actually we are now being presented—the Court is now being presented—with a case of first impression, when it has a full record which you can give full consideration to, and that Gong Lum, which did not squarely raise the issue, ought not to be controlling.

All I am saying is that you do not have to overrule "separate but equal" at the elementary school level in deciding the Kansas case because you have never decided the "separate but equal" applied at the elementary school level.

As I attempted to indicate before, that was a case of first impression, although the Court did not seem to think it was, and that here actually we are now being presented—the Court is now being presented—with a case of first impression, when it has a full record which you can give full consideration to, and that Gong Lum, which did not squarely raise the issue, ought not to be controlling.

All I am saying is that you do not have to overrule "separate but equal" at the elementary school level in deciding the Kansas case because you have never decided the "separate but equal" applied at the elementary school level.

Are you saying that we can say that "separate but equal" is not a doctrine that is relevant at the primary school level? Is that what you are saying?

I think you are saying that segregation may be all right in streetcars and railroad cars and restaurants, but that is all that we have decided.

That is the only place that you have decided that it is all right.

And that education is different, education is different from that.

Yes, sir.

That is your argument, is it not? Isn't that your argument in this case?

Yes.

But how can that be your argument when the whole basis of dealing with education thus far has been to find out whether it, the "separate but equal" doctrine, is satisfied?

You are talking about the gist of the cases in this Court?

I am talking about the cases in this Court.

As I interpret the cases in this Court, Your Honor, as I interpret the Sweatt case and the McLaurin case, the question of "separate and equal," as to whether the separate and equal doctrine was satisfied, I do not believe that that test was applied there. In McLaurin there was no separation.

But take the Gaines case, take the beginning of the "separate but equal," and unless I completely misconceive the cases I have read before I came here and those in which I have participated, the test in each one of these cases was whether "separate and equal" is relevant or whether it was satisfied, and we have held in some of the cases that it was not satisfied, and that in a constitutional case we do not have to go beyond the immediate necessities of the record, and we have said as to others that for purposes of training in the law you have a mixed situation; you cannot draw that line.

Well, take the Gaines case, Your Honor; the only thing that I would say on the Gaines case is that what the Court decided in the Gaines case was that, since there were no facilities available to Negroes, that the petitioner Gaines had to be admitted to the white school.

Now, it is true that there is certain language in the Gaines case which would appear to give support to Plessy v. Ferguson, but the language in terms of the decision—you have to take the language in regard to what the decision stated in the Sipuel case—I think it is the same thing, and when we get over to Sweatt and McLaurin, we have a situation in which this Court went beyond certain physical facilities and said, "These are not as important as these other things that we cannot name," and it decided then to set standards so high that it certainly would seem to me to be impossible for a state to validly maintain segregation in law schools.

In the McLaurin case, without any question of separation, what the Court did was that you have the same teachers and so forth, so there could have been no question of his being set apart, except in the classroom, and so forth—there could be no question of the quality of instruction not being the same. This Court held that those restrictions were sufficient in and of themselves to impair McLaurin's ability to study and therefore to deprive him of the equal protection of the law.

So, in my view, although the Gaines case is a case where you have the language, the decisions really do not hinge on that.

Now, it is true that there is certain language in the Gaines case which would appear to give support to Plessy v. Ferguson, but the language in terms of the decision—you have to take the language in regard to what the decision stated in the Sipuel case—I think it is the same thing, and when we get over to Sweatt and McLaurin, we have a situation in which this Court went beyond certain physical facilities and said, "These are not as important as these other things that we cannot name," and it decided then to set standards so high that it certainly would seem to me to be impossible for a state to validly maintain segregation in law schools.

In the McLaurin case, without any question of separation, what the Court did was that you have the same teachers and so forth, so there could have been no question of his being set apart, except in the classroom, and so forth—there could be no question of the quality of instruction not being the same. This Court held that those restrictions were sufficient in and of themselves to impair McLaurin's ability to study and therefore to deprive him of the equal protection of the law.

So, in my view, although the Gaines case is a case where you have the language, the decisions really do not hinge on that.

In the Gaines case it offered what they called equal facilities, did it not?

They offered facilities out-of-state, out-of-state facilities.

But which they said were equal.

Yes.

The Court said that they were not equal.

Yes, sir; this Court said not only were they not equal, but that the state had the obligation of furnishing whatever facilities it was going to offer within the state.

Well, we did have before us in the Gaines case the problem of "separate and equal." We determined that they were not equal because they were out of the state.

Well, Your Honor, I do not conceive of "separate and equal" as being the type of offering that the State of Missouri offered when they attempted to give out-of-state aid.

Neither did this Court; but Missouri claimed that they were equal.

I am sorry, I do not think you have understood my answer. I do not conceive of the out-of-state aid which Missouri offered to petitioner Gaines to go to some institution outside of the state as being within the purview of a "separate but equal" doctrine. I think that in terms of the "separate but equal" doctrine, that there must be the segregation. The "separate but equal" doctrine, I think, concerns itself with segregation within the state and the setting up of two institutions, one for Negroes and one for whites. All the state was doing, I think, there, was that it knew that it had the obligation of furnishing some facilities to Negroes, and so it offered them this out-of-state aid. But I do not believe that actually it can be—I mean, my understanding is that this cannot be classified as a part of the "separate but equal" doctrine.

No. This Court did not classify it that way. They said it is not separate and equal to give education in another state and, therefore, "You must admit him to the University of Missouri."

The University of Missouri, yes.

Yes.

But there is another aspect of my question, namely, that we are dealing here with a challenge to the constitutionality of legislation which is not just one legislative responsibility, not just an episodic piece of legislation in one state. But we are dealing with a body of enactments by numerous states, whatever they are—eighteen or twenty—not only the South but border states and northern states, and legislation which has a long history.

Now, unless you say that this legislation merely represents man's inhumanity to man, what is the root of this legislation? What is it based on? Why was there such legislation, and was there any consideration that the states were warranted in dealing with—maybe not this way—but was there anything in life to which this legislation responds?

Well, Your Honor, I think that this legislation is clear—certain of this legislation in Kansas—that the sole basis for it is race.

Is race?

Is race.

Yes, I understand that. I understand all this legislation. But I want to know why this legislation, the sole basis of which is race—is there just some willfulness of man in the states or some, as I say, of man's inhumanity to man, some ruthless disregard of the facts of life?

As I understand the state's position in Kansas, the State of Kansas said that the reason for this legislation to be applicable in urban centers, is that although Negroes compose four percent of the population in Kansas, ninety percent of them are concentrated in the urban areas, in the cities of the first class and that Kansas has people from the North and the South with conflicting views about the question of the treatment of Negroes and about the separation and segregation, and that, therefore what they did was that they authorized, with the power that they had, they authorized these large cities where Negroes appeared in large numbers to have segregated public elementary schools.

When did that first appear in the Kansas law?

I am not sure, but I believe in 1862.

In 1862, and the next amendment was 1868?

1862, Mr. Wilson tells me. The legislation on which this statute arose was first enacted in 1862.

That was amended in 1868.

That is right. But our feeling on the reach of equal protection, the equal protection clause, is that as these appellants, as members of a minority group—whatever the majority may feel that they can do with their rights for whatever purpose, that the equal protection clause was intended to protect them against the whims, as they come and go.

How would you establish the fact that it was intended to protect them against them? How would I find out if I liked to follow your scent; that is, what the Amendment is intended to accomplish, how would I go about finding that out?

I think that this Court in, certainly since Plessy v. Ferguson—this Court, and in Shelley v. Kraemer, has repeatedly said this was the basis for the Amendment. The Amendment was intended to protect Negroes in civil and political equality with whites.

Impliedly it prohibited the doctrine of classification, I take it?

I would think, Your Honor, that without regard to the question of its effect on Negroes, that this business of classification, this Court has dealt with it time and time again.

For example, in regard to a question of equal treatment between a foreign corporation admitted to the state and a domestic corporation, where the only basis for the inequality is the question of the residence of the foreign corporation, this Court has held under its classification doctrine that there is a denial of equal protection.

For example, in regard to a question of equal treatment between a foreign corporation admitted to the state and a domestic corporation, where the only basis for the inequality is the question of the residence of the foreign corporation, this Court has held under its classification doctrine that there is a denial of equal protection.

Meaning by that that there was no rational basis for the classification?

Well, I think that our position is that there is no rational basis for classification based on that.

But do you think that you can argue that or do you think that we can justify this case by some abstract declaration?

Well, I have attempted before lunch, Your Honor, to address myself to that point, and that was one of the bases for our attack; that this was a classification, an instance of a classification, based upon race which, under these decisions of this Court, does not form a valid basis for the legislation.

Mr. Carter, you speak of equal protection. Do you make a distinction between equal protection and classification, on the one side, and due process on the other? Is that your contention, that this violates due process?

We do not contend it in our complaint. We think that it could, but we thought that equal protection was sufficient to protect us.

And do you find a distinction between equal protection and due process in this case?

I do not. I think that the Court would, in terms of equal protection and due process, decide that under the equal protection clause and, therefore, do not consider due process. But so far as my understanding of the law, I would say that there would be no real distinction between the two.

I would like to reserve the next few minutes for rebuttal.

I would like to reserve the next few minutes for rebuttal.

General Wilson.

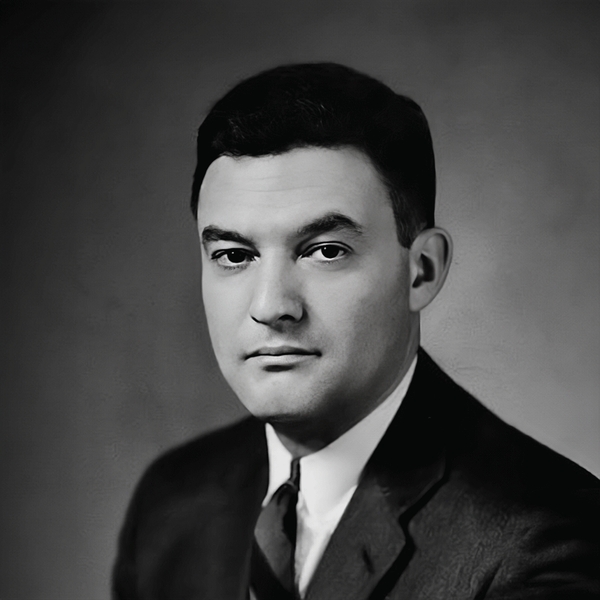

ARGUMENT OF PAUL E. WILSON, ESQ.,

ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLEES

ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLEES

May it please the Court:

I represent the State of Kansas, who was an intervening defendant in this proceeding. The issue raised by the pleadings filed by the State in the court below was restricted solely to the matter of the constitutionality of this statute, and I want to limit my remarks to that particular phase of the subject.

This Court heretofore noted an apparent reluctance on the part of the State of Kansas to appear in this case and participate actively in these proceedings. Because of that fact, I would like to digress for a moment and explain to you the position that the State takes with regard to this litigation.

As my adversary pointed out, the effect of the Kansas statute is local only; it is not statewide. Furthermore, the statute permits, and does not require, boards of education in designated cities to maintain segregated school systems. Pursuant to that statute, the Board of Education of the City of Topeka set up and does operate a segregated school system affecting students in the elementary grades.

Now, this lawsuit in the court below was directed at the Topeka Board of Education. The school system set up and maintained by that board was under attack. The Attorney General, therefore, took the position that this action was local in nature and not of statewide concern. We did not participate actively in the trial of the case.

However, after the trial in the court below there was a change in personnel and a change in attitude on the part of the Board of Education. The Board of Education determined then that it would not resist this appeal. The Attorney General thereupon determined that he should be governed, his attitude should be governed, by the attitude taken on the local level. Consequently we did not appear.

I mention this to emphasize the fact that we have never at any time entertained any doubt about the constitutionality of our statute.

I represent the State of Kansas, who was an intervening defendant in this proceeding. The issue raised by the pleadings filed by the State in the court below was restricted solely to the matter of the constitutionality of this statute, and I want to limit my remarks to that particular phase of the subject.

This Court heretofore noted an apparent reluctance on the part of the State of Kansas to appear in this case and participate actively in these proceedings. Because of that fact, I would like to digress for a moment and explain to you the position that the State takes with regard to this litigation.

As my adversary pointed out, the effect of the Kansas statute is local only; it is not statewide. Furthermore, the statute permits, and does not require, boards of education in designated cities to maintain segregated school systems. Pursuant to that statute, the Board of Education of the City of Topeka set up and does operate a segregated school system affecting students in the elementary grades.

Now, this lawsuit in the court below was directed at the Topeka Board of Education. The school system set up and maintained by that board was under attack. The Attorney General, therefore, took the position that this action was local in nature and not of statewide concern. We did not participate actively in the trial of the case.

However, after the trial in the court below there was a change in personnel and a change in attitude on the part of the Board of Education. The Board of Education determined then that it would not resist this appeal. The Attorney General thereupon determined that he should be governed, his attitude should be governed, by the attitude taken on the local level. Consequently we did not appear.

I mention this to emphasize the fact that we have never at any time entertained any doubt about the constitutionality of our statute.

General Wilson, may I state to you that we were informed that the Board of Education would not be represented here in argument and would not file a brief, and it being a very important question, and this case having facets that other cases did not, we wanted to hear from the State of Kansas.

We are very glad to comply with the Court's request. I was simply attempting to emphasize that we did not intentionally disregard our duty to this Court.

I understand it.

As I understand it, you had turned it over to the Board of Education and expected them to appear here, is that right?

As I understand it, you had turned it over to the Board of Education and expected them to appear here, is that right?

That is correct, sir.

And when we found out that they were not going to, we did not want the State of Kansas and its viewpoint to be silent.

Now, the views of the State of Kansas can be stated very simply and very briefly: We believe that our statute is constitutional. We do not believe it violates the Fourteenth Amendment. We believe so because our supreme court, the Supreme Court of Kansas, has specifically said so. We believe that the decisions of the Supreme Court of Kansas follow and are supported by the decisions of this Court, and the decisions of many, many appellate courts in other jurisdictions.

In order to complete the perspective of the Court with respect to the Kansas school system, I should like to allude briefly to the general statutes of Kansas which provide for elementary school education. There are three types of municipal corporations in Kansas authorized to maintain public elementary schools. There is the city of the first class, cities consisting of 15,000 or more persons, of which there are twelve in the state; then there are cities of the second class, and cities of the third class, which are included within the common school districts.

Now, this statute, I want to emphasize, applies only to cities of the first class, to those cities which have populations of more than 15,000. It does authorize separate schools to be maintained for the Negro and white races in the elementary grades in those cities, with the exception of Kansas City, where a separate junior high school and high school is authorized.

My adversary has conceded, and the court below has found, that there was no substantial inequality in the educational facilities afforded by the City of Topeka to these appellants. The physical facilities were found to be the same, or substantially alike.

Not only was that finding made with regard to physical facilities, but the course of study was found to be that subscribed by state law and followed in both systems of schools. The instructional facilities were determined to be substantially equal. There was the item of distinction wherein transportation was supplied to the Negro students and not to the white students. That certainly was not an item which constituted one of discrimination against the Negro students.

Therefore, it is our theory that this case resolves itself simply to this: whether the "separate but equal" doctrine is still the law, and whether it is to be followed in this case by this Court.

My adversary has mentioned—again I want to emphasize that the Negro population in Kansas is slight. Less than four percent of the total population belong to the Negro race.

In order to complete the perspective of the Court with respect to the Kansas school system, I should like to allude briefly to the general statutes of Kansas which provide for elementary school education. There are three types of municipal corporations in Kansas authorized to maintain public elementary schools. There is the city of the first class, cities consisting of 15,000 or more persons, of which there are twelve in the state; then there are cities of the second class, and cities of the third class, which are included within the common school districts.

Now, this statute, I want to emphasize, applies only to cities of the first class, to those cities which have populations of more than 15,000. It does authorize separate schools to be maintained for the Negro and white races in the elementary grades in those cities, with the exception of Kansas City, where a separate junior high school and high school is authorized.

My adversary has conceded, and the court below has found, that there was no substantial inequality in the educational facilities afforded by the City of Topeka to these appellants. The physical facilities were found to be the same, or substantially alike.

Not only was that finding made with regard to physical facilities, but the course of study was found to be that subscribed by state law and followed in both systems of schools. The instructional facilities were determined to be substantially equal. There was the item of distinction wherein transportation was supplied to the Negro students and not to the white students. That certainly was not an item which constituted one of discrimination against the Negro students.

Therefore, it is our theory that this case resolves itself simply to this: whether the "separate but equal" doctrine is still the law, and whether it is to be followed in this case by this Court.

My adversary has mentioned—again I want to emphasize that the Negro population in Kansas is slight. Less than four percent of the total population belong to the Negro race.

What is that number?

Sir?

What is that number?

The population of the State, the total population, is approximately two million. The total Negro population is approximately 73,000.

And of those, how many are in the cities of 15,000, about nine-tenths, would you say?

Our brief says that nine-tenths of the Negro population lived in cities classified as urban. The urban classification includes those of 2,500 or more. I should say that two-thirds of the Negro population lived in cities of the first class.

And this, according to your brief, as I remember—the present situation in Kansas is that this segregated class of primary schools are in only nine of those cities?

In only nine of our cities.

As I recall, there are eighteen separate elementary schools maintained in the State under and by virtue of the statute. There is one separate junior high school and one separate high school. In other communities we do have voluntary segregation, but that does not exist with the sanction or the force of law.

As I recall, there are eighteen separate elementary schools maintained in the State under and by virtue of the statute. There is one separate junior high school and one separate high school. In other communities we do have voluntary segregation, but that does not exist with the sanction or the force of law.

Do you have any Indians in Kansas?

We have a few, Your Honor.

Where do they go to school?

I know of no instances where Indians live in cities of the first class. Most of our Indians live on the reservation. The Indians who do live in cities of the first class would attend the schools maintained for the white race.

Those who live on the reservations go to Indian schools?

Yes, sir; attend schools maintained by the Government.

Do any people go to them besides the Indians?

I do not believe so, sir.

May I trouble you before you conclude your argument to deal with this aspect of the case, in the light of the incident of the problems in Kansas, namely, what would be the consequences, as you see them, for this Court to reverse this decree relating to the Kansas law; or, to put it another way, suppose this Court reversed the case, and the case went back to the district court for the entry of a proper decree. What would Kansas be urging should be the nature of that decree in order to carry out the direction of this Court?

As I understand your question, you are asking me what practical difficulties would be encountered in the administration of the school system?

Suppose there would be some difficulties. I want to know what the consequences of the reversal of the decree would be, and what Kansas would be urging us the most for dealing with those consequences in the decree?

In perfect candor, I must say to the Court that the consequences would probably not be serious.

As I pointed out, our Negro population is small. We do have in our Negro schools Negro teachers, Negro administrators, that would necessarily be assimilated in the school system at large. That might produce some administrative difficulties. I can imagine no serious difficulty beyond that.

Now, the question of the segregation of the Negro race in our schools has frequently been before the Supreme Court of Kansas, and at the outset I should say that our court has consistently held that segregation can be practiced only where authorized by the statutes. The rationale of all those cases is simply this: The municipal corporation maintaining the school district is a creature of statute. It can do only what the statute authorizes. Therefore, unless there is a specific power conferred, the municipal corporation maintaining the school district cannot classify students on the basis of color.

Now, the question of the segregation of the Negro race in our schools has frequently been before the Supreme Court of Kansas, and at the outset I should say that our court has consistently held that segregation can be practiced only where authorized by the statutes. The rationale of all those cases is simply this: The municipal corporation maintaining the school district is a creature of statute. It can do only what the statute authorizes. Therefore, unless there is a specific power conferred, the municipal corporation maintaining the school district cannot classify students on the basis of color.

Have there been efforts made to remove the act permitting segregation or authorizing segregation in Kansas?

I recall—I think I mentioned in my brief—in 1876 in a general codification of the school laws, the provision authorizing the maintenance of separate schools was, apparently through inadvertence, omitted by the legislature. It was nevertheless deemed to be repealed by implication. But thereafter, in 1879, substantially the same statute was again enacted. Since that time, to my knowledge, there have been no considered efforts made in the legislature to repeal that statute.

Mr. Attorney General, you emphasized the four percent and the smallness of the population. Would that affect your problem if there were heavier concentrations?

It is most difficult for me to answer that question. It might.

I am not acquainted with the situation where there is a heavier concentration, in other words.

I mean, your statute adapts itself to different localities. What are the variables that the statute was designed to take care of, if any, if you know, at this late date?

My theory of the justification of the statute is this: The State of Kansas was born out of the struggle between the North and the South prior to the War Between the States, and our State was populated by squatters from the North and from the South.

Those squatters settled in communities. The pro-slavery elements settled in Leavenworth, in Atchison, and Lecompton. The Free Soil elements settled in Topeka, in Lawrence, and in Wyandotte. The Negroes who came to the State during and immediately subsequent to the war also settled in communities.

Consequently, our early legislatures were faced with this situation: In some communities the attitudes of the people were such that it was deemed best that the Negro race live apart. In other communities a different attitude was reflected. Also in some communities there was a substantial Negro population. In other communities there were few Negroes.

Therefore, the legislature sought by this type of legislation to provide a means whereby the community could adjust its plan to suit local conditions, and we believe they succeeded.

Those squatters settled in communities. The pro-slavery elements settled in Leavenworth, in Atchison, and Lecompton. The Free Soil elements settled in Topeka, in Lawrence, and in Wyandotte. The Negroes who came to the State during and immediately subsequent to the war also settled in communities.

Consequently, our early legislatures were faced with this situation: In some communities the attitudes of the people were such that it was deemed best that the Negro race live apart. In other communities a different attitude was reflected. Also in some communities there was a substantial Negro population. In other communities there were few Negroes.

Therefore, the legislature sought by this type of legislation to provide a means whereby the community could adjust its plan to suit local conditions, and we believe they succeeded.

You mentioned Topeka as one of the Free State settlements, and that seems to be the subject that is involved here with the segregation ordinances. Is there any explanation for that?

As I explained these matters—I am speculating—we have in Kansas—

Your speculation ought to be worth more than mine.

We have in Kansas history a period of migration of the Negro race to Kansas which we call the exodus, the black exodus, as spoken of in the history books. At that time, which was in the 'eighties, large numbers of Negro people came from the South and settled in Kansas communities. A large number of those people settled in Topeka and, for the first time, I presume—and again I am speculating—there was created there the problem of the racial adjustment within the community.

The record in this case infers that segregation was established in Topeka about fifty years ago. I am assuming that, in my speculation for the Court, that segregation began to be practiced in Topeka after the exodus had given Topeka a substantial colored population.